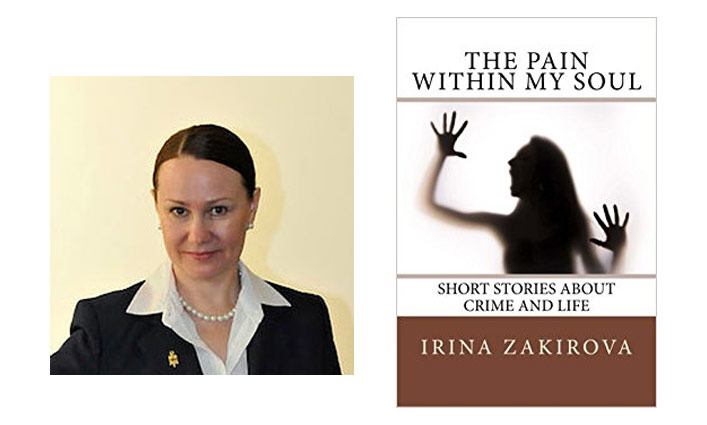

25 years ago, long before she became an adjunct assistant professor at John Jay, Irina Zakirova worked as a police officer in Europe, where she was part of an intelligence unit for an international policing organization. And like most people in law enforcement, interaction with criminals was part of the job. For Zakirova, those interactions soon turned into conversations. She learned about their lives, how they became involved in crime, and the circumstances that led them to become involved with the police. And over the course of time, these conversations began to have a major impact on Zakirova and her perception of crime and criminals.

“I realized that they are not a bad people,” she said. “It’s very primitive to think that way, that criminals are bad people. Certain circumstances, life events, or even coincidence can force them to be in the path of crime.”

The experience of working and speaking with criminals had such an impact on Zakirova that she turned those conversations into stories and published them in her book, “The Pain Within My Soul.” It’s a collection of short, fictional stories based on the real lives of the individuals she spoke with and the journeys that brought them into the criminal justice system.

A quarter century later, Zakirova still wonders what may have happened to them. “Maybe they died, maybe they’re behind bars, and maybe some are in the reintegration process. But I feel bad because I saw what happened with their lives. So there is a pain within my soul for them, because society labeled them as criminals,” she said.

Zakirova said it was her students that first got her thinking about publishing these stories. In the classroom, she noticed that when she used stories and personal experiences to help explain the policies and theories in the textbook, the students found it easier to grasp and far more compelling. For example, in one assignment, students would read one of her stories, and then search through the textbook for a policy that may have helped to prevent the crime that occurred in the story. “They participated, all of the students, and that’s my goal,” she said.

Sometime during one of these assignments, a student produced a drawing – their interpretation of a character in one of the stories. “So the students began to make me think about a gallery,” said Zakirova.

In 2015 Zakirova, who teaches as part of the Department of Law, Police Science and Criminal Justice Administration, and her students organized a college-wide drawing contest where students submitted drawings of their interpretations of the stories in “Pain Within My Soul.” The works were displayed in the Shiva Gallery, but the idea didn’t stop there – Zakirova was soon receiving work from outside the college. Artists from Colombia, Turkey, the Dominican Republic, and other countries read the stories and shared their artistic interpretations with Zakirova, who compiled them into an online gallery (https://www.socartproject.com/books).

According to the gallery website, “These internationally and artistically diverse artists demonstrate their engagement with the existing cultures, and their own civil standing while attempting to provide a new perspective toward identifying and understanding the element which is most often ignored in current studies of crime, but should be thoroughly studied: pain.”

Zakirova is continuing to organize gallery shows, and is currently in negotiations to have a permanent gallery space in Turkey.

This past summer, Zakirova conducted a workshop at the University of Split in Croatia. The workshop was based on her book, using similar techniques where students apply criminology ideas and practices to scenarios found in the stories. Zakirova said she is always surprised at how people from different cultures and ethnicities have very similar reactions to the stories.

“I realized that students from Croatia and John Jay are not very different. They react the same when it comes to injustice. These people are individuals first, only then can we consider them criminals or offenders or not. Behind the scar is the story of the human being.”