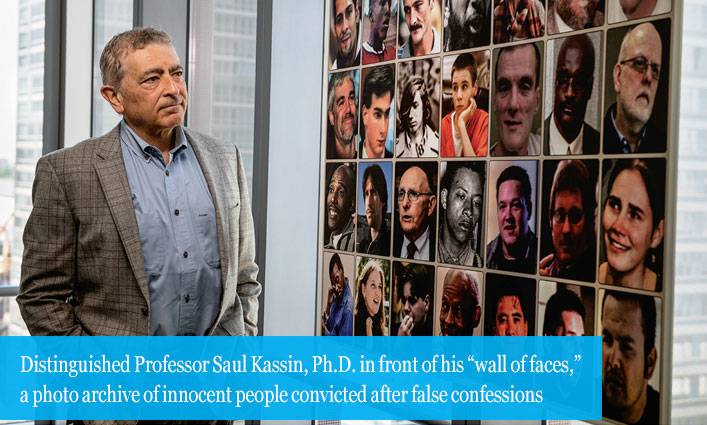

After researching false confessions for over three decades, Distinguished Professor Saul Kassin, Ph.D. has been awarded the James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award from the Association for Psychological Science recognizing his invaluable research contributions. When we see innocent people on the news being released after years of incarceration, feelings of sadness tend to wash over us simply thinking about the unjust trauma these individuals have had to face. But when we find out that the person originally confessed to the offense, the scenario becomes baffling. Why would they confess to something they didn’t do? “There’s no way to know the exact number of people who are innocent but were convicted of a crime because of a false confession—we don’t know what we don’t know—but I can tell you this, about 30 percent of the Innocence Project cases contained false confessions and evidence,” says Kassin. “Most people think that can’t happen to me. But it can happen to you, and it’s more prevalent than most people realize.” We sat down with Kassin to not only congratulate him on this well-deserved lifetime recognition award, but also to better understand why people give false confessions, learn more about his research, and find out how this research can significantly impact policies.

“About 30 percent of the Innocence Project cases contained false confessions and evidence.” —Saul Kassin

Understanding False Confessions

As a trained social psychologist, Kassin was fascinated by and researched how people act as “agents of influence” over others. He continued his postdoctoral work studying juries and jury decision making. After reviewing numerous trials where everybody voted guilty, he came to a realization, they all had confessions. “I would ask people, what’s the basis of your verdict, and they’d all say the confession,” says Kassin. His second realization was on confession evidence. It was eerily similar to a famous obedience experiment where subjects blindly followed an authority’s hurtful commands. “The social psychologist in me said, ‘I hope that everybody they bring into the interrogation room is the criminal, because if they bring in innocent people, they’re going to get innocent people to confess.’”

In 1989, the Central Park jogger case made headlines when five Black and Latinx teenagers between the ages of 14 and 16 confessed to assaulting a white female jogger in the park. Years later, in 2002, the real assailant confessed to the crime and the five men were exonerated. Kassin, a native New Yorker, remembers the case all too well. “I was the only one studying confessions in 1989, and I probably trusted confession evidence less than anyone. That Central Park case always gnawed at me. I knew something was wrong,” says Kassin, who was later asked to review the confession of the actual offender. “They were innocent teenagers. Five false confessions in a case in midtown Manhattan when the whole world was watching.”

“The person confesses as an act of compliance to the officer. They know they’re innocent, but they can’t take the stress of the interrogation anymore.” —Saul Kassin

Classifying of False Confessions

A pioneer in the study of false confessions, Kassin created a classification scheme of the three types of false confessions. The first type is a voluntary false confession and it has nothing to do with law enforcement. Instead, it’s people stepping up and confessing to a crime they didn’t commit. The reason for the confessions, according to Kassin, can range from people looking for attention, to someone wanting to cover up for a loved one.

The second type of false confession, coerced-compliant, comes as a result of an interrogation, as was the case with the Exonerated Five. “The person confesses as an act of compliance to the officer,” explains Kassin. “They know they’re innocent, but they can’t take the stress of the interrogation anymore. They feel overwhelmed by the threats or promises that have been made, or they’ve been lied to about the evidence.”

The third type of false confession, internalized false confessions, is the one most people have a tough time understanding, notes Kassin. “Internalized false confessions are cases where an innocent person not only agrees to confess as an act of compliance, but they also come to believe in their own guilt. They’ve essentially been persuaded into believing that they are guilty,” he says, citing the example of Martin Tankleff who was wrongfully convicted of killing his parents in 1988 after he falsely confessed to their murders. “Martin had no history of conflict with his parents, yet the officers brought him in as a suspect and interrogated him. Over and over again he tells them how he woke up and found his mother dead and his father stabbed and beaten. He then asks, ‘Can I go to the hospital and be with my family.’ He’s told, ‘Not until the work here is done.’” That unfinished work included detectives lying to Tankleff about evidence found at the scene and lying about his father citing him as the culprit. “At that point, Martin broke down. He said, ‘My father doesn't lie. If he said I did it, then I did it. I have no memory, but I must have done it.’”

“The primary way in which police get confessions from innocent people is that they fool them into it, they trick them into it.” —Saul Kassin

Questioning Interrogation Techniques

While false confessions can be caused by a number of reasons, the belief is that a large number of false confessions are a result of false information told by officers during the interrogation. “The primary way in which police get confessions from innocent people is that they fool them into it, they trick them into it,” says Kassin, pointing to the Reid technique, a two-step process, where officers identify someone who may be a suspect and conduct a basic non-accusatorial interview to learn if they’re lying or telling the truth. If they unscientifically determine that they’re “lying,” then they ratchet up the process. “In step one they are listening to what the person says and watching for how they look when they say it. What’s their demeanor, facial expression, posture, do they avoid eye contact. The claim is that officers who are trained in the Reid technique can determine if someone is telling the truth or lying at a level of 90 percent accuracy. The problem is, they can’t. There’s 50 plus years of social psychology research on human deception detection that show people can’t detect whether someone is telling the truth or not,” says Kassin. “They’re only interrogating the ‘liars.’ Well, that’s great if they can make those identifications, but if they can’t, then they’re bringing innocent people into the interrogation step.”

“When you lie to someone about evidence, when you misrepresent reality, you can change a person’s perceptions, beliefs, emotional state, and memories.” —Saul Kassin

The second part of the process is interrogation. “This part says, now we get them to confess. What that means is that the Reid process of interrogation is by definition guilt presumptive,” says Kassin. “Here’s where the Reid technique gets particularly nefarious. This is the part where if officers don’t have real evidence, they lie about it. They make it up. In this country, it’s legal for police to lie about evidence. When you lie to someone about evidence, when you misrepresent reality, you can change a person’s perceptions, beliefs, emotional state, and memories. Every psychologist knows that misinformation can produce a range of profound effects including false confessions.”

Seeing the Prevalence

Crediting the Innocence Project with helping shed light and change the conversation about false confessions, Kassin is proud of the work the organization has done to help uplift the innocent and give them their freedom back. “Around 30 percent of the Innocence Project’s 375 cases involved false confessions,” says Kassin, recognizing that the numbers could be higher. “But there are all these invisible guilty pleas we don’t know about.” Wanting to dispel myths about false confessions, Kassin warns it can happen to anyone. “People think they’re protected. They need to be less naïve and less complacent. They need to not allow their innocence to set them up for failure. People need to learn how to protect themselves and their children. Ask for a lawyer. Don’t waive your Miranda Rights. Don’t take your innocence for granted.”

“People need to learn how to protect themselves and their children. Ask for a lawyer. Don’t waive your Miranda Rights. Don’t take your innocence for granted.” —Saul Kassin

Hoping for Change

Having worked in the field from the start, Kassin has been able to see how the public’s understanding of false confessions has evolved, and how false confessions cause incredible harm to the innocent. And while the change to reduce the prevalence of false confession has been slow, and can admittedly be frustrating, Kassin remains hopeful for the future thanks to a bill introduced into the New York State Legislature. “The bill would ban lies about evidence in New York Police departments,” says Kassin, who worked with the Innocence Project to find support for the legislation. “The most important investigative group in Europe wrote a supportive letter saying, lying puts people at risk. Wicklander & Zulawski, the second leading interrogation company in this country, wrote a letter saying, lying puts people at risk. Military investigators, who have formed what is known as the high value interrogation group, wrote letters saying lying puts innocence at risk. And representing psychology, I wrote a supportive letter. Lying about evidence puts people at risk, but with this legislation, we have a chance to stop that lying. I feel a change coming.”