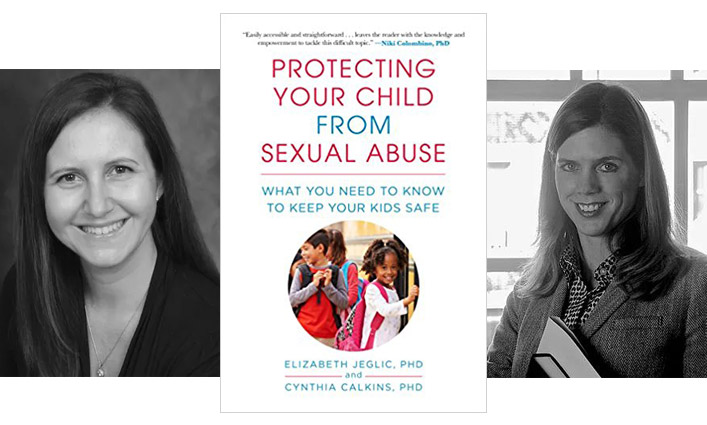

When Dr. Elizabeth Jeglic and Dr. Cynthia Calkins first met as psychology professors at John Jay, they were pleasantly surprised to find that their research interests were remarkably similar. They both were interested in exploring sexual crime and reducing recidivism among sexual offenders. They also soon discovered that they worked well together—so well that they started to collaborate on academic papers, and in 2016, they co-edited a volume titled Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention.

Jeglic and Calkins are also mothers, and in recent years, the professors started to wonder how they could help create a world free from sexual violence for their children. That led them to begin writing a book specifically tailored to parents and guardians on how to protect children from sexual abuse. This February, Jeglic and Calkins published Protecting Your Child from Abuse: What You Need to Know to Keep Your Kids Safe (Skyhorse).

Right now, as the country engages in a national conversation about sexual assault fueled by the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements, Jeglic and Calkins’s research is an important contribution to the conversation on eradicating sexual violence. Jeglic and Calkins say that the best way to stop sexual abuse is to prevent it from happening in the first place, but current policies and laws are ineffective at doing so. This is partly because policies are often not informed by data, but popular misconceptions. For example, despite the fact that 7% of children are abused by a stranger, the myth of “stranger-danger” remains rampant. “Cases involving strangers snatching children from parks are often the ones that get reported in the media,” say Jeglic and Calkins.

The prevalence of those stories in the media has in part led to the implementation of ineffective policy like sex offender registries and residence restriction laws. Sex offender registries are particularly ineffective because a whopping 95% of sex crimes are committed by someone who’s never committed a sexual offense before. “We’re spending the lion’s share of our resources on the 5% who reoffend,” say Jeglic and Calkins. “But we need to focus on what we can do to prevent people from offending in the first place.”

Their research has implications not only for sexual prevention laws, but also for educational and economic policies: sexual violence might be prevented if children from low-income families have access to the same educational resources that their wealthier peers often have. “Most of the individuals who were abused as children reported that it happened when they were in the community without parental supervision,” they say. “One avenue for prevention may be to provide afterschool and summer programming for families that can’t afford it.”

When Jeglic and Calkins were still in graduate school 20 years ago, there was not much research being done on how to prevent sexual violence. While there still remains a great need for data to make better-informed sexual violence prevention programs, the professors are proud to see that interest in the field is flourishing, especially among their own students. “Many of the students in our lab are passionate about the work and bring their own research questions and perspectives to the table,” they say. “Much of our work is done in conjunction with our students. We could not have accomplished what we have so far without the amazing John Jay students who will be the future leaders in the field.”