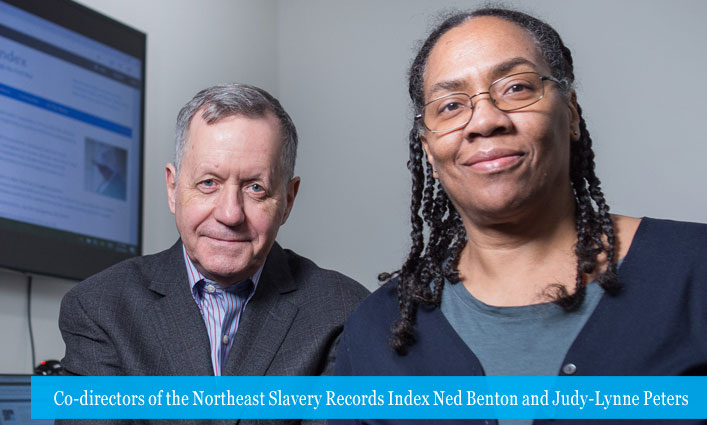

Professor Judy-Lynne Peters, Ph.D. was awarded a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) to support the Northeast Slavery Records Index (NESRI), which she co-directs with Professor F. Warren “Ned” Benton, Ph.D. The grant will “give us the ability to expand our Index tremendously and help us and our research partners find records of enslavement, build our resources, and deepen the understanding of enslavement in the region,” says Peters.

“The Index is an online searchable compilation of records that identify individual enslaved persons and enslavers in the states of New York, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey,” says Benton of the NESRI, which is accessible to the public. “Using our records, communities can educate their members and understand their history of enslavement more efficiently and completely.”

“The Index makes people rethink who they are, how they got to where they are, and the notion of privilege and racism in the United States.” —Judy-Lynne Peters

Why was the NESRI created?

NB: In 2017, I was a member of the Mamaroneck Historical Society and my wife published the Larchmont Gazette. The historical society and Gazette wanted to take a deep dive into the history of enslavement in Mamaroneck. Most people’s concept of enslavement is that it only happened down south, but what they don’t understand is that enslavement first happened in the North. I mentioned the research to Judy-Lynne who said, “Let’s bring this to campus.”

JP: When Ned presented his research to our students here at John Jay, the students sat there slack-jawed because they had no idea that slavery had occurred in New York. Students were rightfully outraged but wanted to learn more, so I recommended that we replicate his research in New York City and the entire state, identifying enslavers and enslaved people. We began by researching and indexing newspaper accounts, birth, census, manumission, cemetery, and other government records. That’s how the New York Slavery Records Index came to be in 2018. Then it evolved into the Northeast Slavery Records Index.

How have people reacted to the Index?

JP: Everyone who has become aware of it has said it’s an eye-opening experience. It makes you realize how little you know about the United States. Where we are today is a direct function of where we were 100 to 200 years ago. I think this information changes people’s perceptions of race and of themselves. I’ve spoken to people reconciling themselves to the fact that their families were enslavers or that they benefited—even if they weren’t directly involved—from people being enslaved. The Index makes people rethink who they are, how they got to where they are, and the notion of privilege and racism in the United States. The more people are exposed to this information, the more they begin to understand the real history.

“Most people’s concept of enslavement is that it only happened down south, but what they don’t understand is that enslavement first happened in the North.” —Ned Benton

How will this grant help improve and expand the NESRI?

JP: The grant will enable us to really drill down and get the information we didn’t have access to previously. There are documents out there in people’s homes, community church records, and historical societies that can add dimension to the history of enslaved people. Once those documents are found, we can digitize and include them in our project, expanding our view into the past.

What are your future goals for the NESRI?

NB: I’d like to see the Index incorporate DNA information. It may help us discover the hidden genealogy of enslaved people. We’ll be able to find connections not just among enslaved people in different households but biological relationships between an enslaved person and enslaver, an enslaved person and someone else in the community, and bring that line of connection to today.

“Our research can give names to these unknown enslaved people. It can show that they lived, recognize their humanity, and give them dignity.” —Judy-Lynne Peters

JP: I would like to see us work in other states and with other institutions. If we can connect with other databases, we might be able to know where people went and how they lived their lives beyond their enslavement in the northeast. I’d also love for the public to contribute to our records. People have family bibles where they document who lived, died, and got married. It’s a treasure trove of information that can empower additional research.

Our research can give names to these unknown enslaved people. It can show that they lived, recognize their humanity, and give them dignity. Through the Index, we’ve re-establishing that connection with our past. It’s not a pretty history but its one worth knowing and sharing.