A couple of years after David Brotherton first arrived to John Jay in 1994, he received a curious invitation from Professor Luis Barrios to visit the church where Barrios preached uptown. It was at Barrios’ Episcopalian church that Brotherton, who had done research on gangs in California, first met Latin King leader Antonio Fernandez, a.k.a. King Tone.

“We want to change the world,” King Tone told Brotherton. “What do you want?” Brotherton responded: “I want to write your story.”

That was the beginning of a years-long relationship between Brotherton and the Latin Kings that would eventually culminate in the book Gangs and Society: Alternative Perspectives, edited by Louis Kontos, David C. Brotherton, and Luis Barrios. During that time, Brotherton hosted the first major gang conference since the 60s, here at John Jay, to help further understanding of what street gangs actually did.

“These guys produced music, spoken word, dances,” says Brotherton. “You couldn’t call them a gang, so we had another term, ‘street organization.’ If you look at it from a different angle, it’s not just violence and guns. It’s a culture. These guys were fighting back against their marginalization and the only way they knew how is through this culture.”

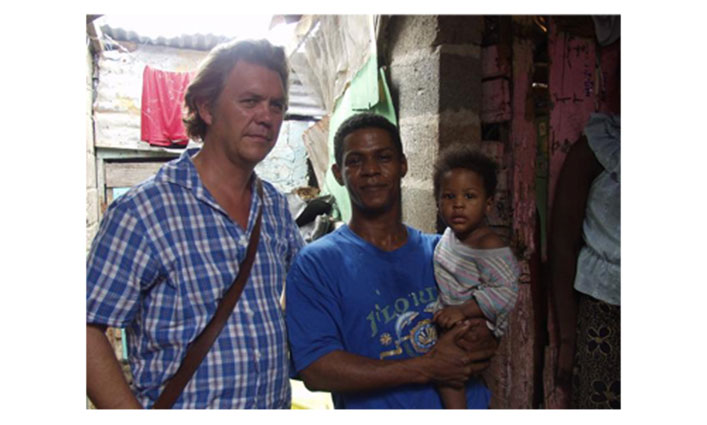

Brotherton continued to work with the Latin Kings and even traveled to Ecuador to document the effects of Ecuador’s legalization of gangs—an effort that contributed to an astonishing drop in homicide rates. But by the early 2000s, Brotherton became interested in another problem: thousands of people in New York, many in the Washington Heights area, were being deported. From 2002 to 2003, Brotherton moved to the Dominican Republic to find out what was happening, and held the first conference on deportees in the Caribbean with an attendance of 1,200 people from several countries. It was an eye-opening experience.

“Most of these deportees were completely assimilated, total New Yorkers,” says Brotherton. “But they were raised during the crack era and got into the mix somewhere along the line, and then the laws became harsher and harsher. It wasn’t that they were so horrible. It was that we became more and more punitive.”

Now, Brotherton’s newest book, Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment, examines the different aspects of deportation, which he says make up a larger deportation regime. “ICE, detention camps, the court system—it’s all interconnected,” he says. “But from a sociological standpoint, how does it fit together? We still don't know.”

To answer that question, Brotherton created a group at John Jay and the CUNY Graduate Center called the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime, made of up several workgroups that look at the different aspects of deportation. At John Jay, this work is particularly relevant. “Deportation in America is totally involved in criminal justice,” Brotherton says. “Many cases that should be purely administrative are now completely mixed up in the criminal justice process.”

“Deportation in America is totally involved in criminal justice. Many cases that should be purely administrative are now completely mixed up in the criminal justice process.” –David Brotherton

For a college with a diverse student population, some of whom are targeted by punitive deportation laws, investigating immigration policy and deportation is especially important. “Students or their family members are personally under threat,” Brotherton says. “If you look at deportation laws, they draw from a racially exclusionary history and use language from the Indian Removal Act and the Runaway Slaves Act. Our detention laws are similar to the Japanese detention laws of the 1930s. As a Hispanic Serving Institute, we need to know those histories and how the continuities of those histories are now playing out in a different era.”