The first stop on the Honors 2020 Alabama Civil Rights trip was Selma, Alabama. Students, faculty, staff, and friends gathered together in The National Voting Rights Museum & Institute and listened to Sam Walker, a historian and guide who actually marched from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama with Martin Luther King, Jr. and current Georgia Congressman John Lewis, when he was only 11 years old. Walker dramatically took the group back in time when black folks in Alabama bravely fought for their right to vote. He explained how the white community during that time used every method possible to deter blacks from voting—locking the doors to the “colored entrance” of the courthouse where you could register to vote, arresting activists who handed out voting rights information, and even lynching people who dared to speak out about the injustice.

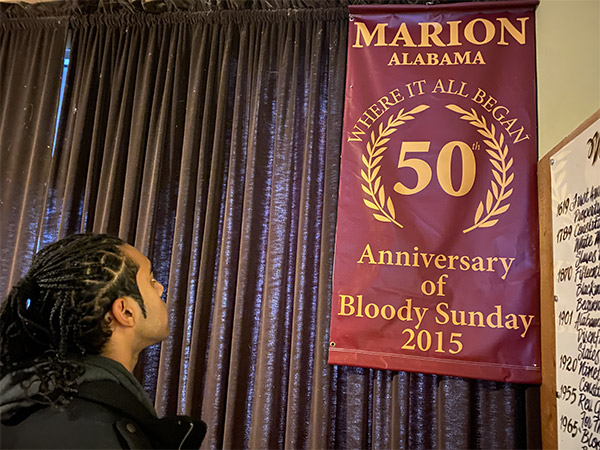

Walker told the group that the tipping point that led to the march was the death of a young man by the name of Jimmy Lee Jackson. A confrontation broke out between civil rights workers and law enforcement officers in Marion, Alabama. Jackson attempted to protect his elderly grandfather from being beaten, and a state trooper shot him for doing so. Days later Jackson passed away. His murder sparked three voting rights marches from Selma to Montgomery. The first took place on Sunday, March 7, 1965. When Walker explained how the peaceful marchers, including a young Lewis, were met with tear gas and billy clubs on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he asked the group what the event was called. They all solemnly replied, “Bloody Sunday.” Walker went on to explain how the second march resulted in a standoff at the bridge between the activists and law enforcement, causing King to turn around in the hopes of getting federal support. He closed his talk by depicting the final, successful march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, that took five days. It was the march that Walker himself walked alongside his civil rights heroes.

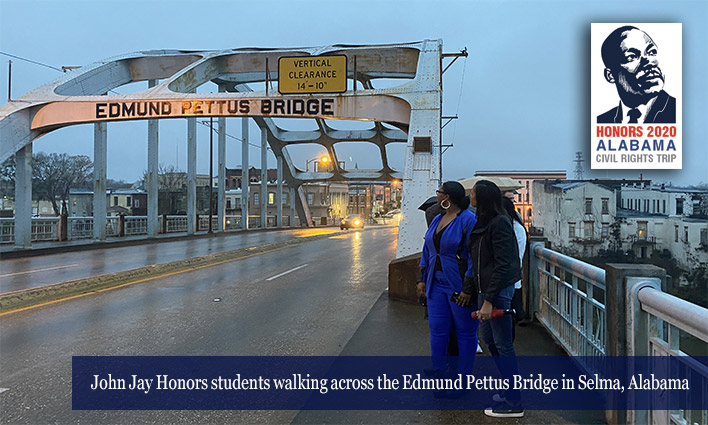

After exploring the museum, the group walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge—which was named after a confederate officer and the head of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan—and gathered in a voting rights memorial garden to explore their thoughts and feelings.

“People are not afraid to express their blatant prejudices. It’s scary because I really have to watch my back depending on where I am.” —John Francois

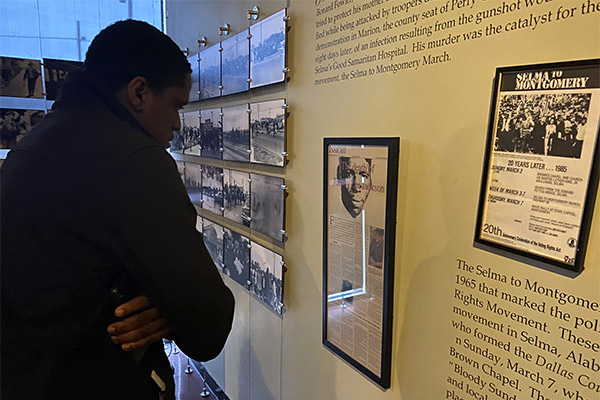

John Francois ’21, looking at a museum exhibit about Jimmy Lee Jackson

Looking at this, and hearing about his death, honestly, it invokes anger in me a little bit. It’s just a mix of emotions and I’m not really sure how to sort them out. That could have been me, or someone that I knew. It can still be me today. People are not afraid to express their blatant prejudices. It’s scary because I really have to watch my back depending on where I am. In the Caribbean, where I’m from, you wouldn’t have someone saying, “Hey you’re black, get out of here.” But this can still happen in certain parts of this country.

“They shoved 20 people into a small jail cell like this. Our speaker told us that he was placed in a cell like this when he was only 11 years old.” —Kayla Hayman

Kayla Hayman ’23, whose grandmother marched in Selma, looking at the recreated jail cell within the museum

I wasn’t expecting to walk into such a hands-on exhibit. Standing within these bars just makes what they experienced more powerful to me. The activists had to spend a really long time in these jail cells just for the right to vote. They shoved 20 people into a small jail cell. Our speaker told us that he was placed in a cell like this when he was only 11 years old. I can’t imagine 11-year-old me doing something like this.

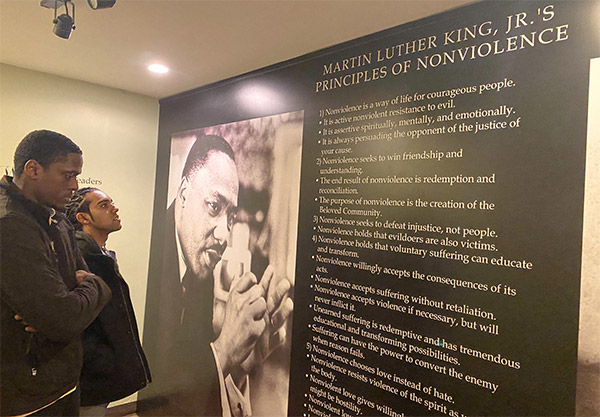

“Even after slavery was abolished, they were still living in a form of slavery. Those acts were domestic terrorism.” —Tyler Johnson

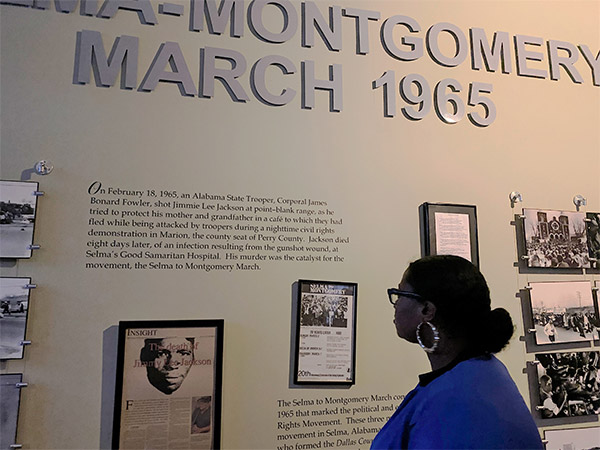

Tyler Johnson ’22, reading about the voting rights march

The most powerful thing that I learned was that our presenter was actually arrested at the age of 11 for cleaning up the campsites during the march. Being so young, and having your childhood just stripped away from you. It didn’t matter what age you were, it was your black identity that stood out, and they treated you like an animal. It was just very dehumanizing. Even after slavery was abolished, they were still living in a form of slavery. Those acts were domestic terrorism.

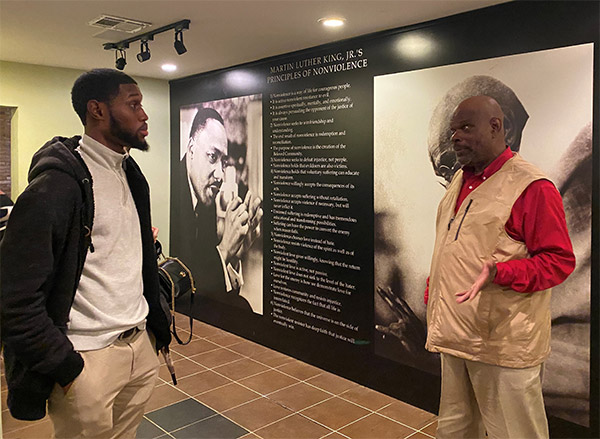

“They didn’t value his life at all because of the color of his skin.” —Malik Monteith

Malik Monteith ’23, viewing a voting rights remembrance

I was shocked hearing how a reverend—who was just handing out papers about voting rights—was pulled over and arrested. Then, right in front of another black man who was cleaning the police station, the officers plotted to lynch the reverend. Obviously, they didn’t think of the reverend as a human being. They didn’t value his life at all because of the color of his skin. It’s not shocking because you know the history, but it really makes it real because you see the story in just one person, a person who was there.

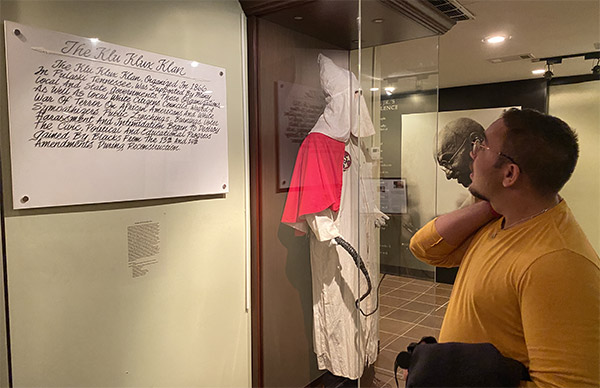

“Seeing that exhibit left a weird feeling in my stomach and it made me feel very uncomfortable as an African-American man. It was sick and twisted and came from a place of ignorance.” —Christian Bethea

Christian Bethea ’23, explaining the cruel voting “tests” blacks were subjected to in order to register to vote

Just to be able to vote, the black citizens had to take tests that white citizens didn’t have to take. They called it a “literacy test,” but in many cases it didn’t really test whether you could read or write. It was just something that was extremely difficult and almost impossible to pass, in order to keep a black person from voting. They’d have a big jar of jelly beans and they would ask the black person to say exactly how many jelly beans were in the jar. They could only vote if they guessed the exact number correctly. They did the same thing with cotton balls in a jar, but that had an even more evil meaning behind it because African-Americans were not too far removed from slavery and being subjected to picking cotton. Seeing that exhibit left a weird feeling in my stomach and it made me feel very uncomfortable as an African-American man. It was sick and twisted and came from a place of ignorance. That’s why it’s so important for us to vote now. People fought hard for us to have that right.

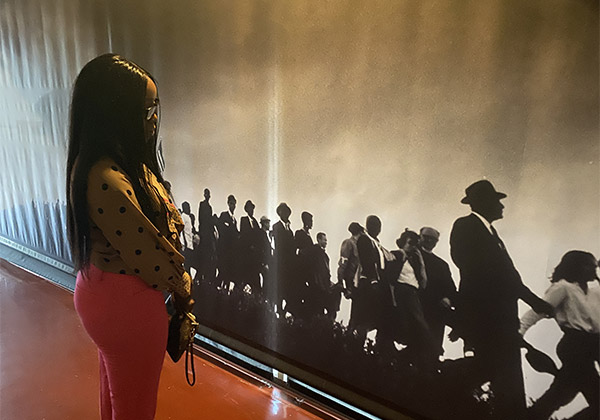

“Walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge was epic for me. I felt like I was going back in time, but I didn’t feel animosity. I felt a sense of peace.” —Humanchia Serieux

Humanchia Serieux ’20, contemplating the brave actions of Congressman John Lewis

Bloody Sunday was the most barbaric thing. Black people were simply fighting for their right to vote. Right where I just walked, Congressman John Lewis was brutally beaten. He was a young man and his history is so powerful. Walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge was epic for me. I felt like I was going back in time, but I didn’t feel animosity. I felt a sense of peace. Yes, more work needs to be done, but I know that everything is going to be okay.

More scenes from day one of the Honors 2020 Alabama Civil Rights trip:

- Honors 2020 Alabama Civil Rights Trip: Pre-Trip Excitement and Expectations

- Honors 2020 Alabama Civil Rights Trip: A Conversation with John Jay President Karol V. Mason

- Honors 2020 Alabama Civil Rights Trip: An Introspective Essay From Denny T. Boodha ’22

- Honors 2020 Alabama Civil Rights Trip: A Reflective Poem From Isaac Paredes ’21