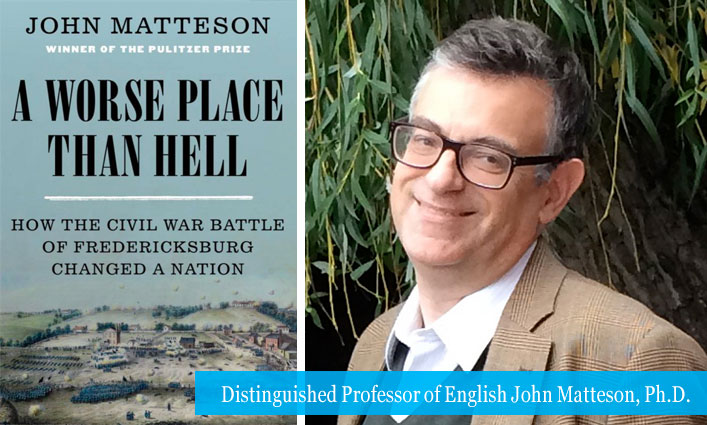

The newest book by Distinguished Professor of English, and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, John Matteson, Ph.D., pulls a page right out of U.S. history. In A Worse Place Than Hell: How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation, Matteson encapsulates the lives of five historical figures—Louisa May Alcott, Walt Whitman, Arthur Fuller, John Pelham, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.—detailing how their fateful encounters with the battle of Fredericksburg, shaped their lives and the landscape of American history, literature, and politics. For Matteson, this was a story long in the making. His fascination with 19th-century America can be traced back to his early childhood. “From the time I was 12 or 13, I was captivated by the Civil War. I would go to sleep at night replaying famous battles in my mind,” he says. “This project was a great opportunity for me to finally write about the Civil War, which had been rattling around in my head for decades.”

Researching the Past

With each book that Matteson writes, he acquires a new library due to the intense nature of conducting and gathering historical research. “I had a sense of what each of these historical figures’ contributions were and where to find the documents I needed. The Whitman papers are all published, but Arthur Fuller is at the other end of the spectrum, nobody had ever bothered to publish his letters,” he says. Matteson leafed through the archives of Houghton Library at Harvard, spending seven hours a day hand-transcribing material. “I was the first person at the door when they opened in the morning. It takes time and dedication, but conducting archival research is fun, and there’s usually a surprise to it.” Matteson’s biggest surprise was a historical finding that corrected an inadvertent error made by Louisa May Alcott, the famed author of Little Women, which altered how historians piece together her life today.

Alcott began her career as an army nurse when she was 30 years old. She ended up having a very meaningful, possibly romantic, encounter with a young soldier who had been wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg. “In her diary, she wrote that he was 30 years old and that he was from Virginia,” says Matteson, noting that Alcott researchers and scholars had never been able to find the mysterious soldier because, “they were all looking for him based on wrong information.” Matteson came across one archive that led him in a different direction. “I blew the whole thing wide open. I found out that he was 21 years old, and he was from Western Pennsylvania. I even found out that his house burned down when he was seven years old, the name of his siblings, the name of his regiment, and exactly where he would have been on the Fredericksburg battlefield when he was wounded. None of this information was known to anyone who had studied Louisa May Alcott in the past,” he says. Matteson’s contribution to accurately preserve Alcott’s legacy and correct a historical inaccuracy is something that gives him a sense of pride.

“After President Lincoln found out what a catastrophe Fredericksburg had been, he said to a friend, ‘If there is a worse place than hell, I’m in it.’ And that’s where the title of the book comes from.” —John Matteson

Reconstructing History

The American Civil War, 1861-1865, fought between the North and the South, most notably over the continuation of the practice of slavery, sets the stage for the five extraordinary lives explored in Matteson’s book. “For the first couple of years of that four-year war, it looked as if the South was going to win,” he says, further explaining how Union leadership under General George McClellan led to the disaster at Fredericksburg. “In December of 1862, McClellan sent his army across the river into the city of Fredericksburg. He then sent wave after wave of Union troops up a hill called Marye’s Heights, but at the top of the hill was Robert E. Lee’s army and they were dug in. They had infantry units behind a stone wall, which is about an eighth of a mile long, and it was just the right height to put your rifle on,” Matteson says. The Union Army was left demoralized and beaten at the end of the battle. “After President Lincoln found out what a catastrophe Fredericksburg had been, he said to a friend, ‘If there is a worse place than hell, I’m in it.’ And that’s where the title of the book comes from.”

“War wasn’t just about people who ended up becoming famous. A lot of it was fought by people who had their moment and then were forgotten.” —John Matteson

Telling Their Stories

At the beginning of the Civil War, American poet Walt Whitman’s career was at a standstill. Louisa May Alcott was still a developing writer and not the literary giant she is considered today. Arthur Fuller, the most unknown of Matteson’s characters, was a chaplain of the 16th Massachusetts infantry regiment who had lost sight in one eye as a child but insisted on serving in the Union Army. On the other side of history was prodigy and West-Point trained John Pelham, the son of an Alabama physician and plantation owner, who fought for the Confederate Army. The last of Matteson’s historical lineup, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who Matteson considers the hero of the book, was a soldier for the Union Army who would go on to serve as a Supreme Court Justice. “I start the book and end with him because he outlives everybody else by more than 30 years, even after getting shot in the neck. He is more important in the history of the Supreme Court than all of the justices, except for maybe two or three,” says Matteson. Unlike Fuller and Pelham, Holmes Jr. did not see battle at Fredericksburg because of dysentery. Instead, he suffered survivor’s guilt after his fellow soldiers were killed at the battle, leaving him the only survivor of his regiment. For all of these individuals, this historical event would forever change how they would be remembered.

“It was interesting to see how one historical event shaped the lives of these five people, most of whom went on to change America,” says Matteson. Whitman’s life was transformed as a poet when his brother George Whitman was listed as a casualty of war in a local newspaper. “Walt Whitman jumped onto a train, went down to Washington, D.C. and got a pass to the Union line to find George,” he says. At the front of the battle, not only did Whitman find George alive, he also found a purpose and a cause worthy of his contributions. “After seeing the injured soldiers, Whitman immediately applied for a government job and spent his spare time visiting wounded soldiers in the hospital, bringing them food, tobacco, reading letters to them, and writing letters for them. Walt Whitman’s greatest work of poetry, Leaves of Grass, would never have been what it was had it not been for the Civil War and the battle of Fredericksburg. American poetry is different because of Whitman, his brother, and what happened at Fredericksburg.”

The same can be said of Alcott, whose renowned literary work titled Hospital Sketches would not have existed had it not been for her encounter with the young, injured soldier who inspired the book and served as the hero. “Hospital Sketches put her on the map and eventually led to the opportunity to write Little Women, which is the oldest book for children written in America and is the foundation of American children’s literature. We would not have it if it were not for Fredericksburg,” he says.

Characters like John Pelham, who stood on the wrong side of history, allowed Matteson to explore the dichotomy between someone held up as an "accomplished individual" but who also defended and practiced the abhorrent practice of slavery. “At Fredericksburg, he takes one single cannon, rides out beyond where the rest of the Confederate troops are, and he holds off the advance of about a third of the Union Army for about an hour with just one cannon. This was a guy who everybody would have thought was great all the way through if he had been born in Ohio instead of Alabama. What he enables me to do is explore the character and the tensions of somebody great for the wrong side, and therefore not great,” he says.

For Matteson, the inclusion of less-famed figures, like Arthur Fuller, serve as a reminder of the many lives claimed by the battle. Fuller, driven to frontlines out of sheer determination and patriotism, charged into Fredericksburg under Confederate sniper fire before being shot to death. “War wasn’t just about people who ended up becoming famous. A lot of it was fought by people who had their moment and then were forgotten.”

“As far as the notion of sacrifice goes, I think John Jay students appreciate the importance of sacrifice, maybe more so than the average person. A lot of students come to John Jay because they have this public service gene, which can be really inspiring.” —John Matteson

Inspecting the Past Through a Modern Lens

Though Matteson’s book is set in the past, he believes that it helps us reflect on the choices we make in the present. “What I would like John Jay students to come away with is some kind of understanding about how large issues and small issues come together,” says Matteson. “We can talk about the Civil War in a big sense as the beginning of justice in America because it ends slavery, but even in this event, which is a step forward in American justice, a lot of things happened that weren’t fair. What I want to do here with this book is to remind people of the importance of individual sacrifice, about how these things don’t come easily, and about how important they are as we move forward in our history.” Hard work, perseverance, and a strong sense of justice are traits that Matteson sees in many of our John Jay students. “As far as the notion of sacrifice goes, I think John Jay students appreciate the importance of sacrifice, maybe more so than the average person. A lot of students come to John Jay because they have this public service gene, which can be really inspiring.”