Our country has a painful history of racial injustice. It’s a history we need to reckon with, and cruel ideology that we can no longer deny still exists. Our communities of color regularly navigate hostile spaces, face overt acts of racism, and experience racial microaggressions that attack their dignity and their humanity. But silence is complicity. That’s why John Jay students, faculty, and staff are finding ways to protest anti-Black behavior and systemic racism. We’re supporting each other, examining our own feelings and actions, and actively fighting unjust treatment throughout our society.

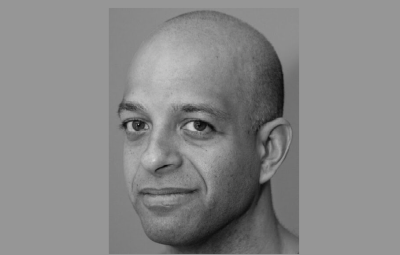

DeCarlos Hines, President of John Jay’s Black Student Union (BSU), knows that when it comes to fighting institutionalized racism, the process for finding solutions has to be bold, strategic, and collaborative. After witnessing multiple Black people being unjustifiably killed in our country, the BSU Executive Board put together a powerful town hall called “What’s Next: Leading the Way in Police Reform” and they wrote a letter to President Karol V. Mason detailing a very specific set of suggestions that could make our curriculum more inclusive and racially sensitive. “We wanted to put in some solutions moving forward that would be beneficial for the College as a whole, and also be beneficial for all the students passing through John Jay,” says Hines. “We want every student to experience a curriculum that touches on race issues—institutional racism, systemic oppression, the psychology of oppression, and ethnicity.” We sat down with Hines to better understand the thinking behind the BSU’s suggestions.

“We want every student to experience a curriculum that touches on race issues—institutional racism, systemic oppression, the psychology of oppression, and ethnicity.” —DeCarlos Hines

BSU Suggestion #1: The College provides mandatory, online anti-racism training for all faculty, staff, and students, the same that is required for the SPARC/Title IX training.

Hines: We have Title IX training because we want people to know what harassment is and that we will not tolerate it at our institution. But why isn’t racism treated the same way? Why not have people be more aware of their biases. We know from research that when people are made aware of certain biases, they tend to do them less. They become very mindful of those biases.

BSU Suggestion #2: All incoming students, both freshmen and transfers, must be required to fulfill six-hours of mandatory anti-racism training, just the same as they are required to take a freshman or transfer seminar.

Hines: The online training in the first suggestion is entry level; it just opens the door. Sitting behind a screen and listening to a video is very different from being in the room with your peers, hearing how they feel and receiving their feedback. The learning environment is much greater when we’re in the same room together. We need to have an environment where people can have a dialog about race issues, where people can have the opportunity to ask questions and discuss biases in the open. We need to sit together and have this discussion.

“We need to have an environment where people can have a dialog about race issues, where people can have the opportunity to ask questions and discuss biases in the open.” —DeCarlos Hines

BSU Suggestion #3: As a core requirement, all students must choose from at least two Africana Studies courses. One in their first year at the College, and one as a requirement for graduation in their final year.

Hines: When we look at race and ethnicity in America, it’s broad. When we look at policing in urban communities, who lives in urban communities? People of color. When we look at institutional racism, who are the beneficiaries of institutional racism and who is hurt by institutional racism? When we look at the psychology of oppression, who fits into those categories? It’s not really about Africana Studies classes, it’s about what the students are learning in these classes. When you look at the history of America, any time Black people fought for rights—like the Civil Rights Movement—everyone benefited, including women and all people of color.

If we have minors such as Police Studies and Criminology, why aren’t courses studying racial issues mandatory for them? How can we send students out to work in law enforcement and not educate them about race issues? We’re doing our students, and the community, a disservice not requiring that they take classes that could teach them about racial inequalities. Six years ago, CUNY had ethnic course requirements. They were required. So, I can’t hear any foolishness that making these courses required is impossible. It’s not.

BSU Suggestion #4: Hire professors of color who truly believe in community policing. Those who look beyond the statistics, and see the plight of Blacks in this country as victims of oppression rather than criminals.

Hines: We are in an institution that has a student population that’s 80 percent minority students, and a professor population of 80 percent white professors. Right now, our department chairs are 90 percent white. That in itself is disparaging. That doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. These professors have a difficult time understanding what their students of color are facing. They don’t quite understand the nuances of minorities.

In terms of research, the vast majority of the people who are doing research are white people. We can’t control how aware people are when they do their research, but we can control if a professor puts that information into context when he or she presents it—explaining that these are communities who have been oppressed. We need professors who are going to talk about things like the disparities in education and look at the whole picture, not just statistical analysis. We have to retrain our professors and introduce trauma-informed pedagogy.

Watch the BSU Town Hall “What’s Next: Leading the Way in Police Reform”