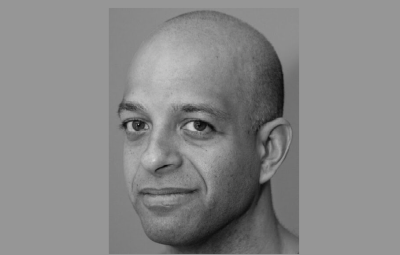

Growing up on the Lower East Side in Chinatown, New York, alumnus David Chong ’80 never really thought about the police. “Except to avoid them,” he says with a laugh. “I lived in a housing development with my mother. The only interactions I had with the police was when they would chase us away from hanging out in groups.” After his family relocated to Queens, New York, discos went into full swing and Chong worked security at one of the trendy discotheques. “It was during that ‘Son of Sam’ period and it was really kind of a tumultuous time,” says the current White Plains Safety Commissioner, who has over 22 years of New York Police Department (NYPD) service under his belt.

One day, after cleaning up the disco in the wee hours of the morning, Chong and some friends went to Jones Beach. As the sun started to rise, his friend’s father—who happened to be an NYPD police officer—told the young men that the “PD” was hiring. He instructed them to go to a public school in Greenwich Village, pay $5, show their driver’s licenses, and take the police exam. “We kidded with him and said, ‘Who wants to pay $5 to take an exam?’” says Chong. Nevertheless, he took the exam and aced it. “I didn’t see very many Asian-Americans taking the exam, but about three months later, I got a card from the Department saying that I passed. I actually scored 100 on the exam.” We sat down with Chong to learn more about his journey in the NYPD and his September 11th experience.

Finding John Jay College

After Chong passed the civil service exam, the idea of becoming a police officer became more real. “I didn’t know anything about policing, so I started to ask around and everyone said, ‘If you want to be a police officer, you should go to John Jay College.’” Once he earned an associate degree from Queensborough Community College, Chong enrolled at John Jay and was determined to get his bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice. As he was taking classes, he steadily moved through the background investigation needed to join the NYPD. “They offered me the job in 1979, but I deferred because I had one semester left at John Jay. In 1980, I graduated and joined the NYPD,” he says. Since he looked younger, Chong immediately went undercover in the Flying Dragons gang. “After a couple of years we took down a big gang investigation and I went to the police academy, which led me to a really good career with 22 and a half years with the NYPD.”

“I remember it being so surreal. People were jumping to their death from such a high place.” —David Chong

Surviving September 11

In 2001, Chong graduated from the FBI National Academy and was serving as a Lieutenant in the Organized Crime Investigations Division. “On September 11th, I had to go downtown to the CCRB [Civilian Complaint Review Board], which was located at 40 Rector Street and was basically right beside the North Tower of the World Trade Center on West Street,” Chong recalls. “I remember that it was a beautiful, sunny morning. As I was driving down the FDR Drive, headed toward the Towers, I was looking at the horizon. The Twin Towers were always a part of the New York City skyline. I couldn’t remember the City without them.”

On his way into the building, he grabbed a copy of the New York Post. “I remember reading some kind of gossip about Mick Jagger’s daughter. Then I heard this tremendous boom and the entire building at 40 Rector Street shook.” Everybody at the CCRB started running around and panicking. A young woman came up to Chong and informed him that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. The thought seemed absurd to him. How could a plane hit the World Trade Center? Maybe it was a little passenger jet that lost its course? He thought to himself. “To my shock and absolute dismay, when I exited on Rector Street I saw that it was a major airline that hit the North Tower. I saw part of the plane on West Street. I felt the heat and it was just raining down debris. I started to see body parts, and being a detective, the first thing on my mind was to look for a pen to mark the human body parts,” says Chong, shaking his head in disbelief of what he witnessed. He saw massive amounts of people standing around, looking up, frozen in complete shock. “I remember it being so surreal. People were jumping to their death from such a high place. I remember seeing one body bounce against a building and just break into pieces.”

Amidst absolute pandemonium, Chong knew he had to get civilians away from the scene. “As I made my way to the North Tower, I was screaming at people to run. I was yelling, ‘Run north! Run away from the Towers!’” When he got to the North Tower, security was advising people to go to the South Tower, which was not hit at the time and was where they were setting up a triage area. In his suit and tie, with his badge pinned to his jacket, Chong ran into the South Tower. “I remember hearing over a police radio that another airplane was coming in. I looked up into the sky and I saw an airliner swim inside the South Tower. I thought it was a nightmare.”

“I looked up into the sky and I saw an airliner swim inside the South Tower. I thought it was a nightmare.” —David Chong

As a first responder, you’re trained not to take an elevator when something is burning. Chong saw an officer carrying two oxygen tanks and heading for the stairwell. “I said, ‘Give me a tank and I will come upstairs with you. He handed off a tank and we made it up between the 11th and 12th floors. What I remember the most is the smells. Smells of the burning building, smells of jet fuel, smells of burning flesh, all the smells that I still smell at nighttime in my sleep.” His senses of smell and sight intensified in the chaos; while his hearing muffled down to a low hum of sirens and screaming.

He saw two exhausted men bringing down a woman who was very badly burned. All three of them were covered in blood. “I remember saying to a young firefighter behind me, ‘Go over there and help these people.’ He said, ‘I don’t know who you are, but you can’t take me away from my group. I’m in full rescue equipment. You’re in a suit and tie. I think it’s better that you help them out.’” The young fireman’s logic made sense to Chong and he watched as the fireman climbed up the stairwell. After he took the hurt woman from the arms of the two men, he instructed them to get out of the building as fast as they could.

Chong tried to administer oxygen to the injured woman, but panic set in and he couldn’t get the tank to work. “I remember she was speaking Spanish to me and talking about her niños, which were her children. I told her, ‘Stay with me. We’re going to go downstairs. The ambulances are downstairs and you’re going to see your children once we get to the ambulances.’” As he helped her down the stairs and they stumbled through the lobby, he took off his suit jacket and covered her exposed body. Chong looked out onto Church Street and saw the flashing lights. We just have to make it to those flashing lights, he thought to himself. She’ll be okay if we make it to the flashing lights. “As we were walking, the floor opened up like a sinkhole. I lost my grip of her. Never saw her again,” says Chong, visibly still shaken from the experience.

Being Rescued

As the building collapsed, Chong fell in between two concrete barriers that most likely saved his life. Two officers from the NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit walked by and saw his arm frantically pushing against the ground. Chong could hardly breathe. The air was thick and his nose and mouth were filled with dirt and blood. “I was hurting so bad, but the adrenaline was going so heavy. I was trying my best, reaching and hoping that she was beside me, but I couldn’t feel anything,” says Chong. Until they saw the gun on his belt, the Emergency Service officers who pulled him out of that concrete cocoon had no idea that he was also NYPD. Chong’s badge was on his jacket, and his jacket was wrapped around the badly burned woman. He implored the officers to help him find the woman. “I was just crawling on my hands and knees through the rubble looking for this woman. Then one of them said. ‘We have to go. We are getting a warning that the other tower is going to collapse.’” The two officers dragged Chong across Broadway by his armpits and dove into the Century 21 department store. The windows had all been blown out. Clothing, racks, and countertops were strewn across the floor. The two officers protectively covered Chong’s body with their bodies, and as the second Tower came down, a gush of wind and thunderous noise filled the air.

Living With the Trauma

In 20 years, a day hasn’t gone by without Chong remembering the woman he lost in the lobby of the South Tower, the young fireman he watched go up the stairs, or the horrific sights and smells that arrested his senses. He lives his life battling Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and cancer. “I have survivor’s guilt. I don’t know why I ended up between those two concrete barriers,” he says. “The terror of that day has affected me forever.” In the days, months, and years following the attack, the detective in Chong wanted justice, and the survivor in him was angry. “When you’re a New York City police officer, and you investigate a crime, you have a bad guy to go after. Our bad guy was Osama Bin Laden and he was in Afghanistan.” Chong joined the NYPD’s Counterterrorism Bureau as the Commander of the Global Intelligence and Analysis Unit. His message to the next generation is to never forget what happened. “They should know the sacrifices of the people that were there. We lost so many police officers and firefighters that day. Those are the people who are the real heroes.”